Since February this year, the EU and the UK have been negotiating a draft withdrawal agreement. If the agreement is concluded, at least a transition period until the end of 2020 can be counted on. At the moment, however, this is anything but certain – conflict-prone issues such as the Northern Ireland controversy and the future acceptance of decisions of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) could still lead to failure. Then we would be faced with a “hard” BREXIT.

What do companies have to prepare for?

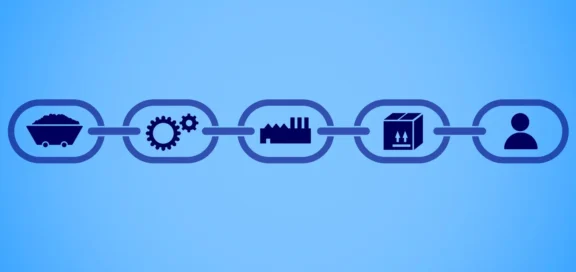

BREXIT will have a particular impact on existing and new contractual relationships between companies from Great Britain and the remaining 27 EU countries. If the UK and the EU do not form a customs union, imports in both directions will become more expensive for buyers. Exporters will suffer competitive disadvantages and will have to take cost-cutting measures to remain competitive. Customs formalities can make supply relationships more complicated and time-consuming. The European VAT system will no longer be applicable (elimination of the “reverse charge” principle). Products from Great Britain will no longer have their origin in the EU, and supplied parts will no longer be considered “local content”. This has implications for the applicability of free trade agreements.

There are also legal uncertainties.

Under product liability law, for example, the company that imports a product from a country outside the European Economic Area is considered to be the manufacturer of the product. In the event that a manufacturer in Great Britain purchased components from the USA or China, the British manufacturer has so far been considered a manufacturer of these supplied parts. As soon as the UK ceases to be a member of the EU, the import of British products will be considered as an import into the European Economic Area, thus the German importer will be regarded as the manufacturer of the product as a whole – including the components from the USA or China.

The regulations on judicial cooperation will no longer apply vis-à-vis the UK. This means that both the question of the law applicable to a contract and the question of the location of jurisdiction will no longer be answered by Brussels Regulations with a uniform EU-wide answer. The enforcement of judgments from an EU member state in Great Britain and vice versa will become considerably more difficult. At least the old European Convention on Jurisdiction and Enforcement of 1972 will apply again in the relationship between Germany and the UK, but this Convention was only concluded by a handful of other states (France, Belgium, Greece, Italy, Ireland, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Portugal, and Spain). Moreover, the bureaucratic requirements under the old Convention are much higher than at present.

What can companies do today to counter the negative consequences of BREXIT in contract law?

- For new agreements with partners in the UK, contractual arrangements should be made today which provide for an adjustment of the conditions in the event of a “hard” BREXIT. Although, for long-term contractual relationships that already existed at the time when Great Britain announced its withdrawal from the EU (i.e. in March 2017) it is possible to demand a contract adjustment considering the “rebus sic stantibus”-doctrine, this possibility does not apply to new contracts. In this case, adjustment or special termination clauses must be made from the outset with regard to, for example:

– the introduction of customs duties

– changed VAT conditions

– Incoterms. - Distribution contracts can no longer refer to the EU as a whole to define the territory of the contract. The UK should be explicitly mentioned if it is to be included.

- The applicable law must not be left to chance. It is essential to provide for a choice of law clause, as it is not possible to predict which statutory provisions will apply to the contract in the UK in the future. Against the background described above, the UN Convention on the International Sale of Goods (CISG) should not – as is unfortunately so often the case – be automatically excluded.

- The same applies to jurisdiction clauses. Arbitration clauses are more frequently called for, in particular with regard to enforceability. The enforcement of arbitral awards is easily possible in the UK after BREXIT, and vice versa in most EU states, since recognition and enforcement is governed by the New York Convention of 1958, independently of EU membership.

- Current contracts should be examined to see whether they could possibly be terminated before the UK’s exit and concluded again in the light of the prevailing situation.

The “wait and see” approach is therefore not the order of the day. There are numerous possible contractual arrangements, which do not incur any costs, but help to avoid future economic disadvantages.